HL4.1 Global interactions and global power

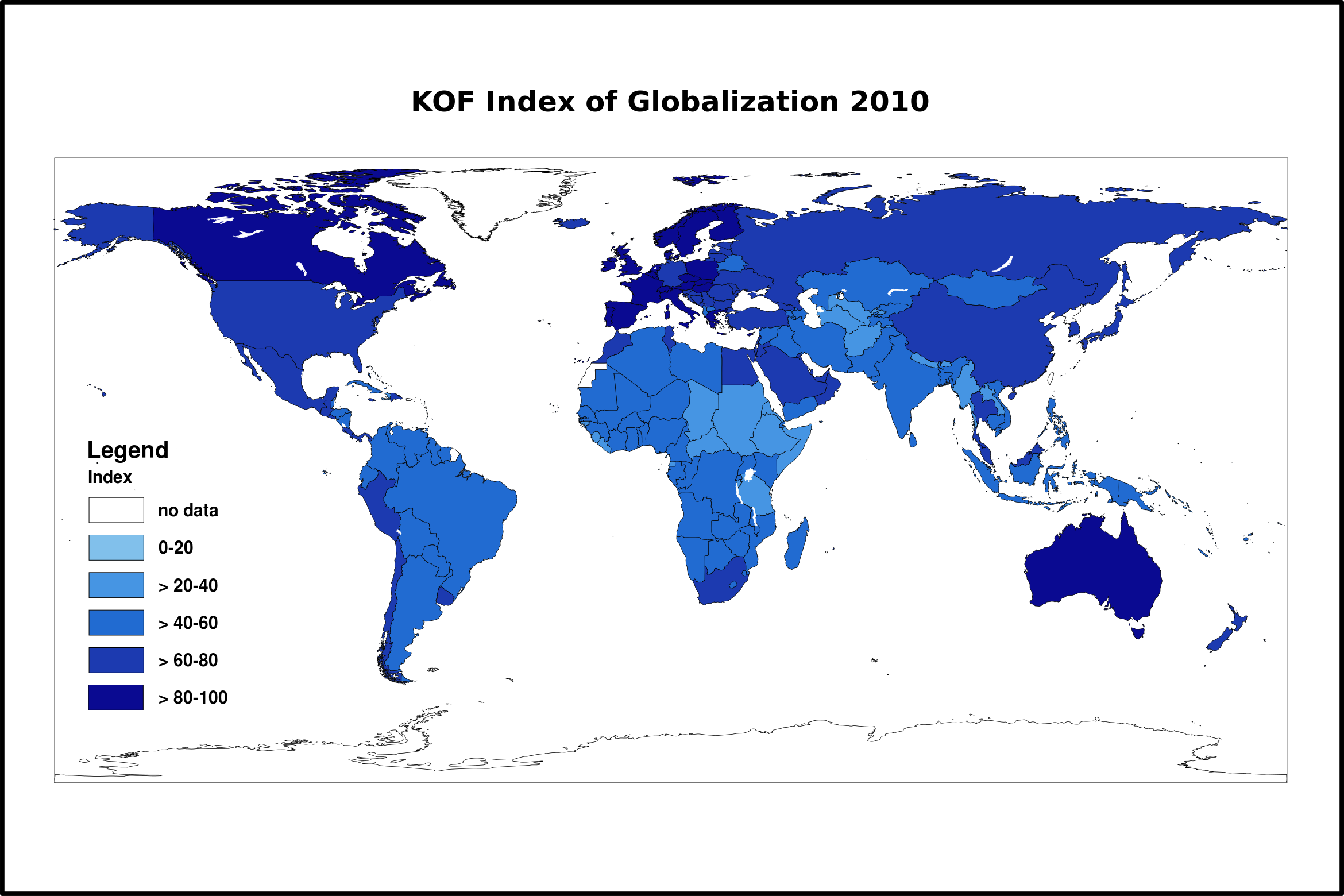

KOF index of globalization

The KOF index of globalization, introduced in 2002, cover the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization. KOF defines globalization as: "the process of creating networks of connections among actors at multi-continental distances, mediated through a variety of flows including people, information and ideas, capital and goods. Globalization is conceptualized as a process that erodes national boundaries, integrates national economies, cultures, technologies and governance and produces complex relations of mutual interdependence".

More specifically, the three dimension of the KOF index are defined as:

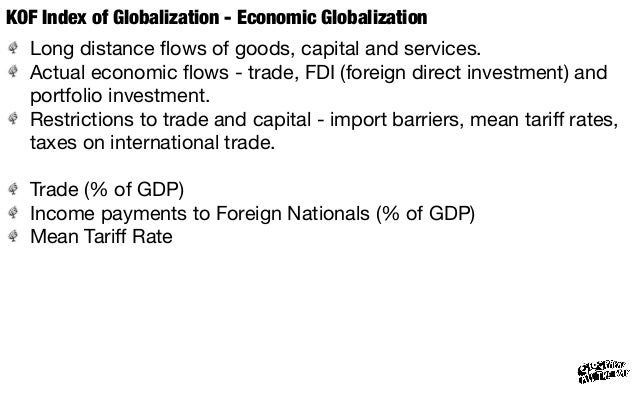

- Economic globalization, characterized as long-distance flows of goods, capital and services, as well as information and perceptions that accompany market exchanges (this accounts for 38% of the globalization index)

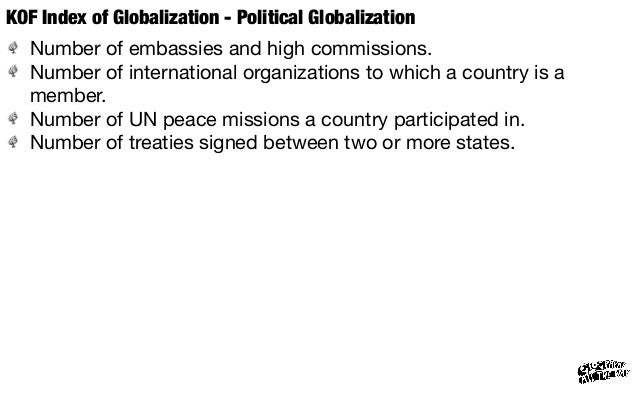

- Political globalization, characterized by a diffusion of government policies (this accounts for 23% of the globalization index)

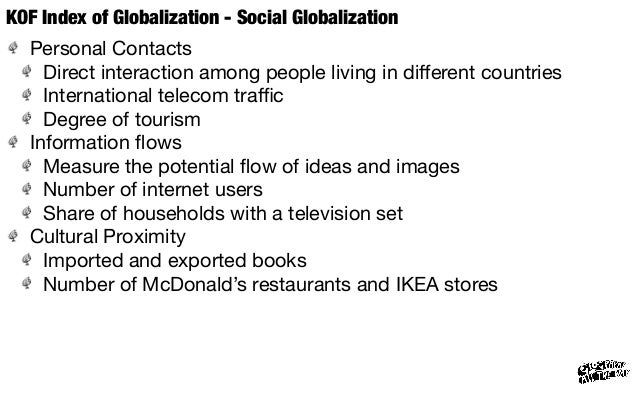

- Social globalization, expressed as the spread of ideas, information, images and people (this accounts for the remaining 39% of the globalization index)

Source: Nagle, Garrett and Briony Cooke. Geography Course Companion. Print.

Source: http://share.nanjing-school.com/dpgeography/hl-course/hl-global-interactions/measuring-global-interactions/

Source: http://www.geographyalltheway.com/in/ib-global-interactions/globalization-index.htm

Global superpowers

Global organizations and groups

G7/8

The Group of Seven (G7) is an informal bloc of industrialized democracies—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—that meets annually to discuss issues such as global economic governance, international security, and energy policy. Proponents say the forum's small and relatively homogenous membership promotes collective decision making, but critics note that it often lacks follow-through and excludes important emerging powers.

Russia belonged to the forum from 1998 through 2014—then the Group of Eight (G8)—but was suspended after its annexation of Crimea in March of that year. The G7’s future has been challenged by continued tensions over Ukraine, concerns over the eurozone's economic performance, and the larger Group of Twenty’s (G20) rise as an alternative forum. Meanwhile, the election of U.S. President Donald J. Trump has thrown the bloc’s traditional commitment to free trade into turmoil and raised questions over its cooperation on global climate policy.

Membership

France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany formed the Group of Six in 1975 (Canada joined the following year) to provide a venue for the non-Communist powers to address pressing economic concerns, which included inflation and a recession sparked by the OPEC oil embargo. Cold War politics invariably entered the group’s agenda.

The European Union has participated fully in the G7 since 1981 as a “nonenumerated” member. It is represented by the presidents of the European Council, which comprises the EU member states’ leaders, and the European Commission, the EU’s executive body. There is no formal criteria for membership, but participants are all developed democracies. The aggregate GDP of G7 member states makes up nearly 50 percent of the global economy, down from nearly 70 percent three decades ago.

G20

What is the G20?

The Group of Twenty (G20) is an international forum that brings together the world's leading industrialised and emerging economies. The group accounts for 85 per cent of world GDP and two-thirds of its population.

Much of the important business takes place on the sidelines and in informal meetings.

Initially attendance at G20 summits was limited to the finance ministers and central bank governors of members, when it was established 17 years ago.

But since an inaugural meeting between G20 leaders in Washington DC following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, summits between G20 leaders themselves have become an annual event.

The first G20 summit occurred in Berlin, in December 1999 and was hosted by the German and Canadian finance ministers.

Since then there have been 18 G20 meetings between finance ministers and central bank governors, and 10 summits between heads of state or government of G20 economies.

The next summit of G20 leaders is scheduled for Hangzhou, China, from 4-5 September 2016. It is the first to be hosted by China, only the second in Asia, and has been hailed as a “milestone” in the country’s development and symbolic of its growing importance as a major power.

Which countries are members of the G20?

The G20 is made up of:

- Argentina

- Australia

- Brazil

- Canada

- France

- Germany

- India

- Indonesia

- Italy

- Japan

- Mexico

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- South Korea

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- United States of America

- China

- South Africa

The final member is the European Union, represented by the European Commission, rotating Council presidency and the European Central Bank (ECB). Spain as a permanent non-member invitee also attends leader summits.

Other countries also attend summits at the invitation of the host country, while it has become customary for the Chair of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) and representatives of the African Union and NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa’s Development) to be present at leader summits.

How often do they meet?

Meetings tend to occur on an annual basis; however leaders met twice a year in 2009 and 2010, when the global economy was in crisis. The last meeting between finance ministers and central bank governors was held in Chengdu, China, in July 2016.

Why isn’t every country invited?

Fearing deadlock in a larger decision-making body, not all countries are invited to the G20.

How does the G20 differ from the G8?

The Group of Eight (G8), established as the G7 in 1976 but renamed after the admission of Russia in 1998, is an international forum for the eight major industrial economies. It comprises: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

However since 2014 Russian membership has been suspended following the country’s annexation of Crimea.

The G8 seeks cooperation on economic issues facing the major industrial economies, while the G20 reflects the wider interests of both developed and emerging economies.

Who chairs the G20 summit?

The G20 has no permanent staff of its own and its chairmanship rotates annually between nations divided into regional groupings.

China holds the chairmanship in 2016, with Germany to take over in 2017, and India the year after. Hosting the summit is an opportunity to set the agenda and lead discussions.

In 2009, when the UK held a special spring summit, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown orchestrated a deal in which world leaders agreed on a $1.1 trillion injection of financial aid into the global economy. The “historic” deal was widely viewed as a success.

Do all member countries exert equal influence?

There are no formal votes or resolutions on the basis of fixed voting shares or economic criteria. However, the lines of informal influence in the organisation trace those of major power politics.

US President Barack Obama dominated the 2014 Brisbane summit, placing climate change at the top of the agenda, despite the reluctance of host nation Australia’s then Prime Minister Tony Abbott to allow the issue such pride of place.

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Our mission

The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world.

The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems. We work with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change. We measure productivity and global flows of trade and investment. We analyse and compare data to predict future trends. We set international standards on a wide range of things, from agriculture and tax to the safety of chemicals.

We also look at issues that directly affect everyone’s daily life, like how much people pay in taxes and social security, and how much leisure time they can take. We compare how different countries’ school systems are readying their young people for modern life, and how different countries’ pension systems will look after their citizens in old age.

Drawing on facts and real-life experience, we recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people's lives. We work with business, through the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD (BIAC), and with labour, through the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC). We have active contacts as well with other civil society organisations. The common thread of our work is a shared commitment to market economies backed by democratic institutions and focused on the wellbeing of all citizens. Along the way, we also set out to make life harder for the terrorists, tax dodgers, crooked businessmen and others whose actions undermine a fair and open society.

OECD at 50 and beyond

Today, we are focused on helping governments around the world to:

- Restore confidence in markets and the institutions that make them function.

- Re-establish healthy public finances as a basis for future sustainable economic growth.

- Foster and support new sources of growth through innovation, environmentally friendly ‘green growth’ strategies and the development of emerging economies.

- Ensure that people of all ages can develop the skills to work productively and satisfyingly in the jobs of tomorrow.

Source: http://www.oecd.org/about/

OPEC

OPEC is a permanent intergovernmental organization of 13 oil-exporting developing nations that coordinates and unifies the petroleum policies of its Member Countries.

In accordance with its Statute, the mission of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its Member Countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was founded in Baghdad, Iraq, with the signing of an agreement in September 1960 by five countries namely Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. They were to become the Founder Members of the Organization.

These countries were later joined by Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973), Gabon (1975) and Angola (2007).

Ecuador suspended its membership in December 1992, but rejoined OPEC in October 2007. Indonesia suspended its membership in January 2009, reactivated it again in January 2016, but decided to suspend its membership once more at the 171st Meeting of the OPEC Conference on 30 November 2016. Gabon terminated its membership in January 1995. However, it rejoined the Organization in July 2016.

This means that, currently, the Organization has a total of 13 Member Countries.

The OPEC Statute distinguishes between the Founder Members and Full Members - those countries whose applications for membership have been accepted by the Conference.

The Statute stipulates that “any country with a substantial net export of crude petroleum, which has fundamentally similar interests to those of Member Countries, may become a Full Member of the Organization, if accepted by a majority of three-fourths of Full Members, including the concurring votes of all Founder Members.”

The Statute further provides for Associate Members which are those countries that do not qualify for full membership, but are nevertheless admitted under such special conditions as may be prescribed by the Conference.

Global lending institutions

World Bank

Our Mission

To end extreme poverty: By reducing the share of the global population that lives in extreme poverty to 3 percent by 2030.

To promote shared prosperity: By increasing the incomes of the poorest 40 percent of people in every country.

The World Bank Group is one of the world’s largest sources of funding and knowledge for developing countries. Its five institutions share a commitment to reducing poverty, increasing shared prosperity, and promoting sustainable development.

- IBRD The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

- IDA The International Development Association

- IFC The International Finance Corporation

- MIGA The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

- ICSID The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

Partnering with Governments

Together, IBRD and IDA form the World Bank, which provides financing, policy advice, and technical assistance to governments of developing countries. IDA focuses on the world’s poorest countries, while IBRD assists middle-income and creditworthy poorer countries.

Partnering with the Private Sector

IFC, MIGA, and ICSID focus on strengthening the private sector in developing countries. Through these institutions, the World Bank Group provides financing, technical assistance, political risk insurance, and settlement of disputes to private enterprises, including financial institutions.

One World Bank Group

While our five institutions have their own country membership, governing boards, and articles of agreement, we work as one to serve our partner countries. Today’s development challenges can only be met if the private sector is part of the solution. But the public sector sets the groundwork to enable private investment and allow it to thrive. The complementary roles of our institutions give the World Bank Group a unique ability to connect global financial resources, knowledge, and innovative solutions to the needs of developing countries.

Criticism of the World Bank and the IMF encompasses a whole range of issues but they generally centre around concern about the approaches adopted by the World Bank and the IMF in formulating their policies, and the way they are governed. This includes the social and economic impact these policies have on the population of countries who avail themselves of financial assistance from these two institutions, and accountability for these impacts.

Critics of the World Bank and the IMF are concerned about the ‘conditionalities’ imposed on borrower countries. The World Bank and the IMF often attach loan conditionalities based on what is termed the ‘Washington Consensus’, focusing on liberalisation—of trade, investment and the financial sector—, deregulation and privatisation of nationalised industries. Often the conditionalities are attached without due regard for the borrower countries’ individual circumstances and the prescriptive recommendations by the World Bank and IMF fail to resolve the economic problems within the countries.

IMF conditionalities may additionally result in the loss of a state’s authority to govern its own economy as national economic policies are predetermined under IMF packages. Issues of representation are raised as a consequence of the shift in the regulation of national economies from state governments to a Washington-based financial institution in which most developing countries hold little voting power. IMF packages have also been associated with negative social outcomes such as reduced investment in public health and education.

With the World Bank, there are concerns about the types of development projects funded. Many infrastructure projects financed by the World Bank Group have social and environmental implications for the populations in the affected areas and criticism has centered on the ethical issues of funding such projects. For example, World Bank-funded construction of hydroelectric dams in various countries has resulted in the displacement of indigenous peoples of the area.

The World Bank’s role in the global climate change finance architecture has also caused much controversy. Civil society groups see the Bank as unfit for a role in climate finance because of the conditionalities and advisory services usually attached to its loans. The Bank’s undemocratic governance structure – which is dominated by industrialized countries – its privileging of the private sector and the controversy over the performance of World Bank-housed Climate Investment Funds have also been subject to criticism in debates around this issue. Moreover, the Bank’s role as a central player in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts is in direct conflict with its carbon-intensive lending portfolio and continuing financial support for heavily polluting industries, which includes coal power.

There are also concerns that the World Bank working in partnership with the private sector may undermine the role of the state as the primary provider of essential goods and services, such as healthcare and education, resulting in the shortfall of such services in countries badly in need of them. As an increasing shift from public to private funding in development finance has been observed recently, the Bank’s private sector lending arm – the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – has also been criticized for its business model, the increasing use of financial intermediaries such as private equity funds and funding of companies associated with tax havens.

Critics of the World Bank and the IMF are also apprehensive about the role of the Bretton Woods institutions in shaping the development discourse through their research, training and publishing activities. As the World Bank and the IMF are regarded as experts in the field of financial regulation and economic development, their views and prescriptions may undermine or eliminate alternative perspectives on development.

There are also criticisms against the World Bank and IMF governance structures which are dominated by industrialized countries. Decisions are made and policies implemented by leading industrialized countries—the G7—because they represent the largest donors without much consultation with poor and developing countries.

Why is the World Bank controversial

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3XX8J8fzYk

IMF

About the IMF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an organization of 189 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world.

Created in 1945, the IMF is governed by and accountable to the 189 countries that make up its near-global membership.

Why the IMF was created and how it works

The IMF, also known as the Fund, was conceived at a UN conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, in July 1944. The 44 countries at that conference sought to build a framework for economic cooperation to avoid a repetition of the competitive devaluations that had contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The IMF's responsibilities: The IMF's primary purpose is to ensure the stability of the international monetary system—the system of exchange rates and international payments that enables countries (and their citizens) to transact with each other. The Fund's mandate was updated in 2012 to include all macroeconomic and financial sector issues that bear on global stability.

Our Work

The IMF’s fundamental mission is to ensure the stability of the international monetary system. It does so in three ways: keeping track of the global economy and the economies of member countries; lending to countries with balance of payments difficulties; and giving practical help to members.

Surveillance

The IMF oversees the international monetary system and monitors the economic and financial policies of its 189 member countries. As part of this process, which takes place both at the global level and in individual countries, the IMF highlights possible risks to stability and advises on needed policy adjustments.

Lending

A core responsibility of the IMF is to provide loans to member countries experiencing actual or potential balance of payments problems. This financial assistance enables countries to rebuild their international reserves, stabilize their currencies, continue paying for imports, and restore conditions for strong economic growth, while undertaking policies to correct underlying problems. Unlike development banks, the IMF does not lend for specific projects.

Capacity Development

IMF capacity development—technical assistance and training—helps member countries design and implement economic policies that foster stability and growth by strengthening their institutional capacity and skills. The IMF seeks to build on synergies between technical assistance and training to maximize their effectiveness.

Over time, the IMF has been subject to a range of criticisms, generally focused on the conditions of its loans. The IMF has also been criticised for its lack of accountability and willingness to lend to country’s with bad human rights record.

Criticisms of IMF include:

1. Conditions of Loans

On giving loans to countries, the IMF make the loan conditional on the implementation of certain economic policies. These policies tend to involve:

Reducing government borrowing – Higher taxes and lower spending

Higher interest rates to stabilize the currency.

Allow failing firms to go bankrupt.

Structural adjustment. Privatization, deregulation, reducing corruption and bureaucracy.

The problem is that these policies of structural adjustment and macro economic intervention make the situation worse.

For example, in the Asian crisis of 1997, many countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand were required by IMF to pursue tight monetary policy (higher interest rates) and tight fiscal policy to reduce the budget deficit and strengthen exchange rates. However, these policies caused a minor slowdown to turn into a serious recession with mass unemployment.

In 2001, Argentina was forced into a similar policy of fiscal restraint. This led to a decline in investment in public services which arguably damaged the economy.

2. Exchange rate reforms. When the IMF intervened in Kenya in the 1990s, they made the Central bank remove controls over flows of capital. The consensus was that this decision made it easier for corrupt politicians to transfer money out of the economy (known as the Goldenberg scandal, BBC link). Critics argue this is another example of how the IMF failed to understand the dynamics of the country that they were dealing with – insisting on blanket reforms.

The economist Joseph Stiglitz has criticized the more monetarist approach of the IMF in recent years. He argues it is failing to take the best policy to improve the welfare of developing countries saying the IMF “was not participating in a conspiracy, but it was reflecting the interests and ideology of the Western financial community.”

3. Devaluations In earlier days, the IMF have been criticized for allowing inflationary devaluations.

4. Neo Liberal Criticisms There is also criticism of neo-liberal policies such as privatization. Arguably these free market policies were not always suitable for the situation of the country. For example, privatisation can create lead to the creation of private monopolies who exploit consumers.

5. Free market criticisms of IMF

As well as being criticized for implementing ‘free market reforms’ Other criticism the IMF for being too interventionist. Believers in free markets argue that it is better to let capital markets operate without attempts at intervention. They argue attempts to influence exchange rates only make things worse – it is better to allow currencies to reach their market level. [criticism of IMF]

There is also a criticism that bailout countries with large debt creates moral hazard. Because of the possibility of getting bailed out it encourages people to borrow more.

6. Lack of transparency and involvement

The IMF have been criticized for imposing policy with little or no consultation with affected countries.

Jeffrey Sachs, the head of the Harvard Institute for International Development said:

“In Korea the IMF insisted that all presidential candidates immediately “endorse” an agreement which they had no part in drafting or negotiating, and no time to understand. The situation is out of hand…It defies logic to believe the small group of 1,000 economists on 19th Street in Washington should dictate the economic conditions of life to 75 developing countries with around 1.4 billion people.”source

7. Supporting military dictatorships

The IMF have been criticized for supporting military dictatorships in Brazil and Argentina, such as Castello Branco in 1960s received IMF funds denied to other countries.

NDB

Synthesis and evaluation

Use the content from this post to answer the following exam question: ‘Explain how wealthy and powerful places exist at varying scales, and how the global map is complex and subject to change’. 10 marks.

Use mark scheme on page 56 from the new syllabus guide (AO3)

No comments:

Post a Comment