B1. Ocean-atmosphere interactions

Ocean currents

Specific heat

Water has an especially high heat capacity at 4.18 J/g*C, which means it takes more heat to warm a gram of water. This is why, throughout the course of a warm summer day, the water in the ocean does not experience a significant change. Land, on the other hand, has a much lower heat capacity, which is usually less than 1 J/g*C.

During the day, sea and land are both heated up by the sun, but as the sea has a higher specific heat, its temperature rise is less than that of the land. As a result, the air in contact with the sea is comparatively cooler than the air in contact with the sea. Now, the cooler the air, higher its density and hence higher the pressure. Thus during the day, air flows from the high pressure region over sea to the low pressure region over land.

At night, the situation is reversed. Now its time to loose heat and once again, the temperature of the land drops faster. This time the sea is at a comparatively higher temperature and therefore the air over the sea is at lower pressure. Air now flows from the land (high pressure) to the sea (low pressure).

The ocean conveyor belt

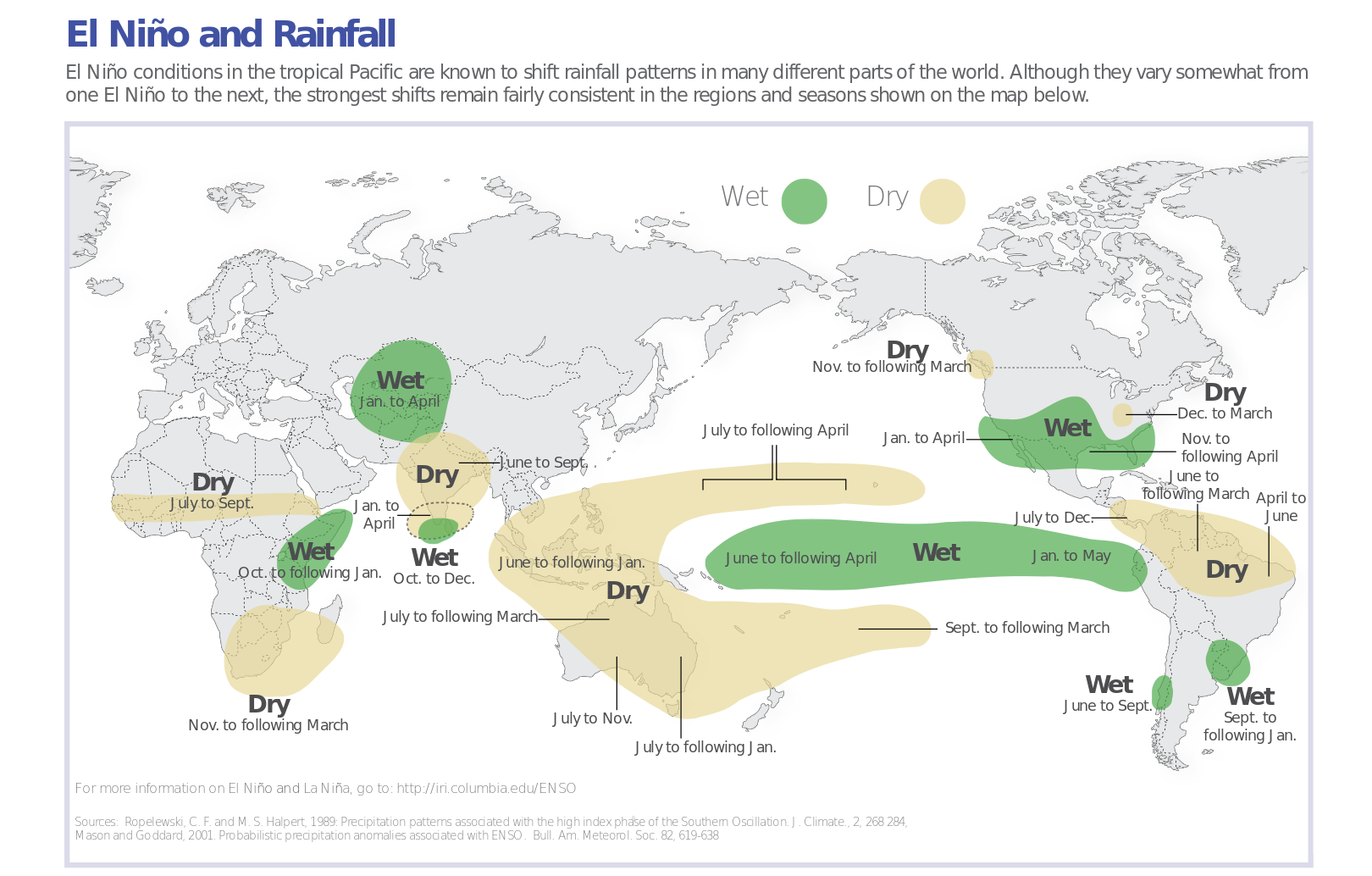

(El Niño-Southerns oscillation (ENSO)

El Nino and La Nina

Tropical storms (hurricanes, typhoons, cyclones)

Hurricanes 101 | National Geographic

Hurricanes are the most violent storms on Earth. People call these storms by other names, such as typhoons or cyclones, depending on where they occur. The scientific term for all these storms is tropical cyclone. Only tropical cyclones that form over the Atlantic Ocean or eastern Pacific Ocean are called "hurricanes."

Whatever they are called, tropical cyclones all form the same way.

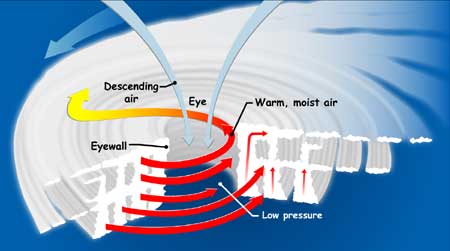

Tropical cyclones are like giant engines that use warm, moist air as fuel. That is why they form only over warm ocean waters near the equator. The warm, moist air over the ocean rises upward from near the surface. Because this air moves up and away from the surface, there is less air left near the surface. Another way to say the same thing is that the warm air rises, causing an area of lower air pressure below.

Air from surrounding areas with higher air pressure pushes in to the low pressure area. Then that "new" air becomes warm and moist and rises, too. As the warm air continues to rise, the surrounding air swirls in to take its place. As the warmed, moist air rises and cools off, the water in the air forms clouds. The whole system of clouds and wind spins and grows, fed by the ocean's heat and water evaporating from the surface.

Storms that form north of the equator spin counterclockwise. Storms south of the equator spin clockwise. This difference is because of Earth's rotation on its axis.

As the storm system rotates faster and faster, an eye forms in the center. It is very calm and clear in the eye, with very low air pressure. Higher pressure air from above flows down into the eye.

When the winds in the rotating storm reach 39 mph, the storm is called a "tropical storm." And when the wind speeds reach 74 mph, the storm is officially a "tropical cyclone," or hurricane.

Tropical cyclones usually weaken when they hit land, because they are no longer being "fed" by the energy from the warm ocean waters. However, they often move far inland, dumping many inches of rain and causing lots of wind damage before they die out completely.

Tropical cyclone categories:

Tropical cyclone categories:

Hurricane case study - Hurricane Matthew

Matthew formed from a tropical wave that pushed off the African coast in late September. That tropical wave was dubbed Invest 97L just southwest of the Cape Verde Islands on Sept. 25.

It took a few days for that system to organize as it moved westward in the Atlantic. About three days later, however, the system gained sufficient organization to be named Tropical Storm Matthew near the Windward Islands.

Once Matthew reached the eastern Caribbean, it became a hurricane and rapidly intensified. Its peak intensity was late Sept. 30 into early Oct. 1 when it reached Category 5 strength with 160 mph winds.

Matthew then made landfall in Haiti and eastern Cuba on Oct. 4 as a Category 4.

From there, Matthew hammered the Bahamas Oct. 5-6 as a Category 3 and 4 hurricane.

The southeastern United States was then hit hard by Hurricane Matthew as it moved very close to the coasts of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. Matthew made one official U.S. landfall on Oct. 8 southeast of McClellanville, South Carolina, as a Category 1 hurricane with 75 mph winds.

Impacts - storm surge

Impacts - wind

Hurricane Matthew South Carolina ~155 MPH wind gusts

Hurricane Matthew kills 276, tears through Haiti, Bahamas, Cuba

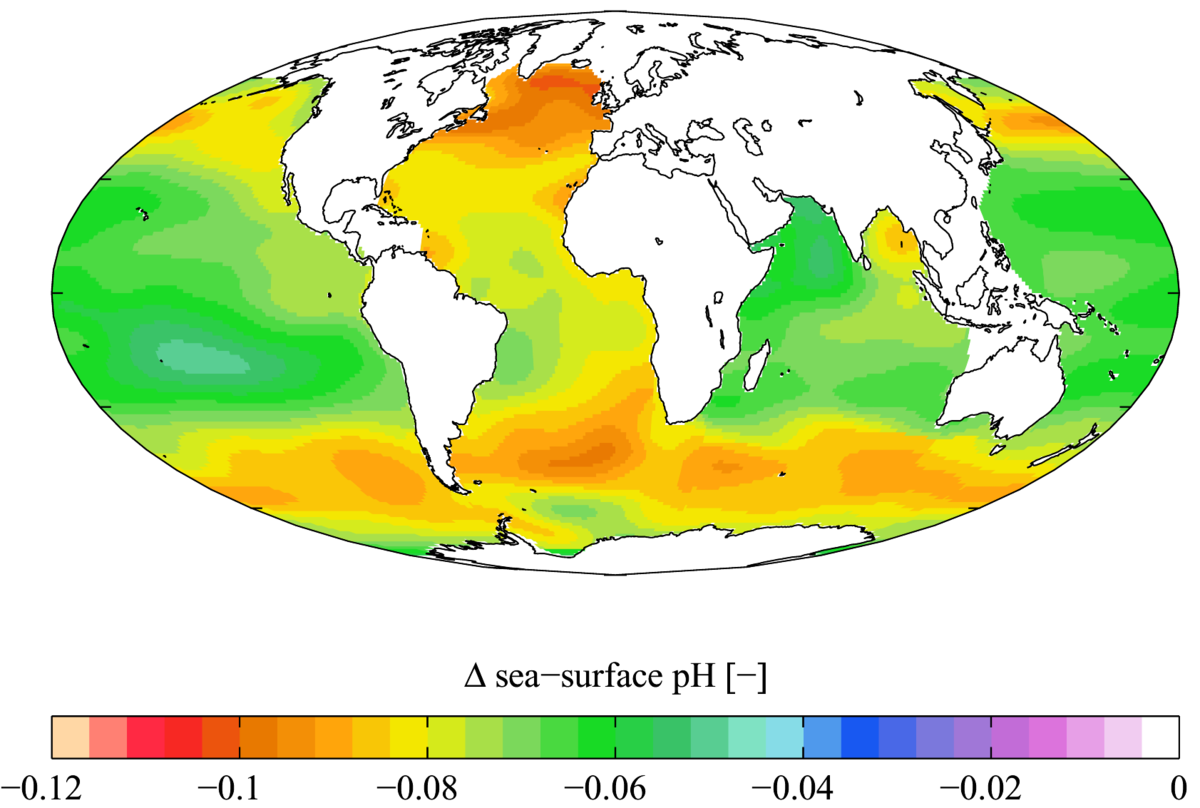

The role of oceans as a source and store of carbon dioxide

No comments:

Post a Comment